Experiencing the Open Atlantic

I recently had the opportunity to join a yacht transfer from the Canaries back to Mainland Europe, over a thousand nautical miles. As I did not have any open Ocean nor multi-day sailing experience yet, I jumped on the offer immediately. Here’s how it went.

Routing

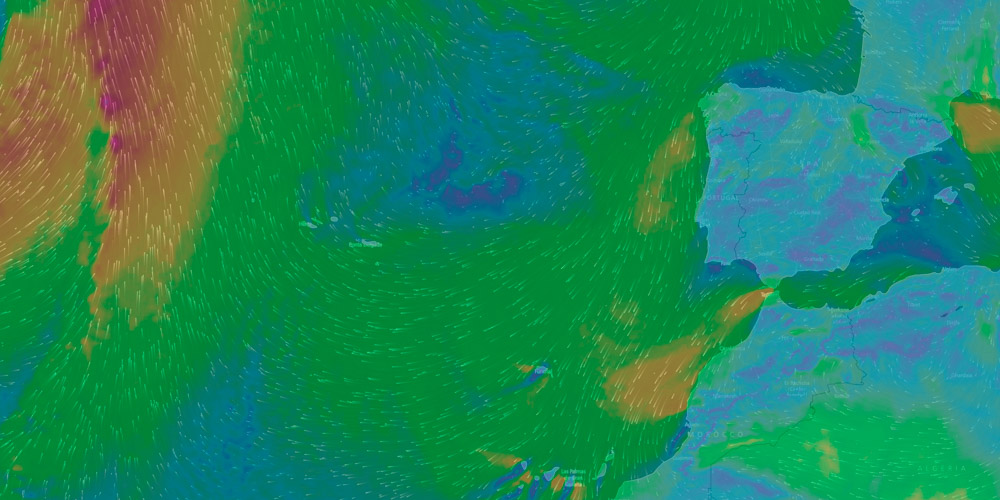

The boat, a Bavaria 46, was located on Gran Canaria (in beautiful Puerto de Mogan) and the checkpoint to reach was Vigo/La Coruña, within two weeks. Depending on the weather, there are usually a few options: To sail the direct route, to stop by Madeira or to go up to the Azores. While the latter is a longer distance, you may be able to round a high pressure weather system comfortably with the wind in your back. GRIB data and services like WindyTV were the tools that helped us decide which routes were feasible and which one to take.

The problem with multi-day weather reports is they often change from day to day. If you are on a longer passage, you might either not find out about these changes until you get into heavy weather or not have the possibility to evade it even though you do know it is coming.

Conditions

The entire crew had their fair share of sailing experience, but few of them had any on the Atlantic. Due to the weather consisting of mostly strong North to North-Eastern winds (the direction we wanted to go) things looked gloomy in general and while there was a suitable high-pressure system (weather picture above is not from the trip), the Azores route was deemed too long in regards to our schedule. Finally, the Madeira route was chosen. It would give us a little rest in between and cover us from heavier weather mid-trip.

The Trip

Due to wind speeds and direction, we waited for an opportunity to leave without exhausting ourselves on the first day. At the end of the third day, the wind calmed and the journey finally started, though with engine support. Motoring through the waves made sleeping fun, like trying to nap on a rollercoaster with an occasional bang from the bow hitting a wave.

The next morning, we got our sails out and tried to sail as close to the wind as possible to approach our goal quickly. We rotated the watch in three shifts of four hours each, twice per day. The boat did not have a wind vane, so we hand-steered throughout the entire trip. My shift was from four to eight, meaning I would see the sun rise around 7:30 am and set around 7:30 pm every day. It also included getting up at 3:30 in the morning, not very pleasant, but I got used to it faster than expected.

Except for a few cases of sea sickness at the start, the passage to Madeira went smoothly and took three days. There, we restocked food and water, took some warm showers and went up the mountains to see the unique vegetation of the island, strongly influenced by the high humidity and constant fog.

After looking at the updated weather reports, the second leg seemed to allow sailing through large parts of the passage, but there was a high probability of hitting heavier weather before reaching Lisbon. The schedule did not allow for a longer wait and some return flights were at risk already, so our alternatives were limited. After one and a half days on the island, we set sail around noon of the eighth day.

This time, everyone knew the ropes already, the boat sailed well and the teams worked together smoothly. We cooked, talked, complained about the boat or spent time reading. It was possible to steer a course directly towards Lisbon while using every opportunity to get further north. We barely saw another boat, and most of the freighters visible on the chart plotter passed us without ever coming in sight. The vastness of the Ocean is different from sailing on a lake or the Baltic Sea. It feels like you have the entire sea to yourself.

On the last one and a half days, the wind picked up. Seven meter waves became normal. With these mountains and valleys passing by, the boat suddenly felt tiny in comparison. Paired with the howling wind, it became an impressive show that cannot be captured through still or moving pictures alone. The base wind went up, 25 knots with gusts of 35 knots. Our last night approached, and the conditions would increase while I went under deck to get some sleep.

Sleeping was hard that night and I noticed we came to a halt multiple times. The sail was also reduced further. Paired with the pitch black darkness outside, the conditions for my next shift promised to become difficult. Once I was dressed, I heard the shout “all hands on deck!”

Before we could do anything about it, the foresail was blown apart in a 45+ knot gust. It had served us well the entire night, allowing for decent speeds throughout. Having lost that, we decided to take down the main sail and start motoring. Getting the sail down in the howling wind, large black waves surrounding us and partially washing over the deck, was a scary but also capturing experience. After we were done, steering without being able to see the waves turned out to be hard. Nevertheless, our wounded boat helped us fight off the elements to the morning, when the strong wind ceased, but the waves remained.

Once we saw land, there were only a few rain showers left to go through. On the evening of the twelfth day, we set foot on mainland Europe again in Cascais after being on the ocean for five consecutive days. Walking turned out to be harder than expected. Lukewarm showers were the best we could get in the Marina. The weather had not only hit us on the outside. The inside of the boat was damp, the mattresses were wet (bad deck repair), so not even the inside of the boat offered much comfort any more.

It was in Lisbon where the teams split up, some (including me) booking other flights as we were going to miss our original ones, the rest taking the boat to the checkpoint. And even though I felt perfectly fine walking around, I woke up for several days after feeling the entire building rock back and forth, with me being periodically pushed into the cushions and lifted up again.

What a Ride

Overall, I am glad I took this opportunity and walked out with many new experiences. The romanticism about offshore sailing has worn off along the way, but it is an unavoidable part of sailing the world. Now, I can consider myself at least somewhat capable of heading into this challenge. Still, I have learned to pay even more respect to the elements.

For people wanting to one day sail the world, I can definitely recommend doing a similar kind of passage.